For Indigenous girls in Brazil, the journey to school is almost longer than the school day itself

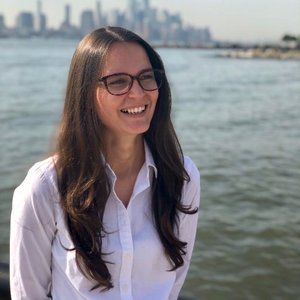

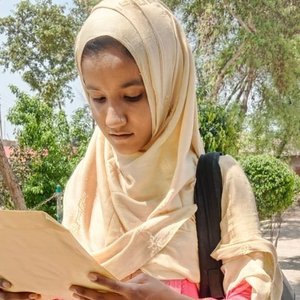

Maikele and Itocovoti are 17-year-old ingenious students from Bahia. (Courtesy of McKinley Tretler / Malala Fund)

17-year-olds Maikele and Itocovoti are fighting against long distances to school, discrimination and low-quality education.

Growing up in her Indigenous community on Brazil’s coast, Maikele Ferreira Nascimento would wake up at 4 a.m. every day to go to the river to bathe. After eating a hearty breakfast of beans and meat with her eight siblings, she would then walk five miles to the school bus. Maikele didn’t have a backpack, so she carried her school supplies in plastic bags to protect them from the heavy rains. If the bus could make it through all the mud, it would be another hour before she arrived at school. It was tiring, Maikele acknowledges, but this is what you had to do if you want to go to school.

Maikele is a 17-year-old Tupinambá, an Indigenous tribe from northeastern Brazil known for their ocean fishing and farming of cassava and corn. Long treks to school, low-quality education and poor roads prevent many Indigenous students like her from learning. In fact, Indigenous populations in Brazil have the highest out-of-school rates in primary and lower secondary school levels in the country. And while Indigenous people represent just 0.5% of the country’s total population, they are 30% of its illiterate population.

17-year-old Itocovoti faces a different set of challenges to completing her education. She is Pataxó Hãhãhãe, a tribe also from Bahia state in northeastern Brazil. The quality of the school in Itocovoti’s Indigenous community was so poor that her parents sent her to a different school in a nearby town. Yet Itocovoti faces discrimination in her new school because she is Pataxó Hãhãhãe. Every day, she says she is “humiliated” and “disrespected” by her classmates who “lack respect for my people and for my culture.”

The discrimination Itocovoti experiences is part of a larger problem of marginalisation and violence against Indigenous peoples that has persisted in Brazil for centuries. Since the mid-1800s, exploitation of natural resources and governmental colonisation programmes have forced Indigenous people from their lands. “Mining interests are turning to our lands to exploit the soil, to extract minerals and rocks,” explained Itocovoti.

Disputes over land continue into present day as Indigenous communities fight to reclaim tribal lands — Maikele’s father was assassinated as a result of a territorial conflict near their village of Serra das Trempes. Her family was forced to relocate to Serra do Padeiro, another Tupinambá community, for their safety.

Living in Serra do Padeiro makes it easier for Maikele to get to school — the bus now picks her up right in front of her house. But Maikele still faces difficulties. “In the rainy season it is almost impossible to have classes,” she says because of the poor roads.

Still Maikele is determined to continue with her education. She remembers what her father used to tell her: “I want my daughters to grow up, go to the university and not to depend on anyone." Maikele hopes to become a lawyer and fight for the land taken from her people. “I want to fulfill my father's dream,” Maikele says simply, “for me and for him.”

Anaí (National Association of Indigenous Action) is an organisation supported by Malala Fund’s Education Champion Network. Anaí works to help Indigenous girls like Maikele and Itocovoti go to school.

Read more

Read more