Off the streets and onto the football pitch

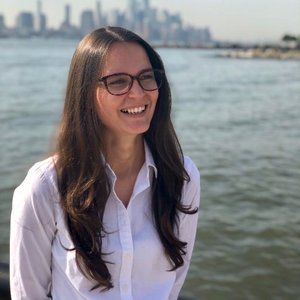

(Courtesy of Família Caracol Facebook)

The girls’ team from a favela in Rio de Janeiro claimed a victory at the 2018 Street Child World Cup.

At the 2018 Street Child World Cup in Russia, the Brazilian girls’ team didn’t speak the same languages as their opponents — so they let their performances on the field do the talking. The girls went undefeated in Moscow and won the cup after a nail-biting final match against Tanzania. “We did what we had to do,” 17-year-old captain Taisa said simply.

The team is from Complexo da Penha, a dangerous favela in Rio de Janeiro. Girls in the community had always been passionate about football, but didn’t have anywhere to play safely. Street Child United Brazil, an organisation that uses football to support children living in vulnerable communities, decided to build a pitch for them — they managed to convince local residents, police and gang members to declare it off-limits to guns and violence.

(Courtesy of Família Caracol Facebook)

Almost a quarter of Rio de Janeiro’s population live in favelas like Complexo da Penha. Overpopulation, poverty and violence are daily concerns for these communities. On average, one Rio resident is hit by a stray bullet every seven hours. The Brazilian police are in constant conflict with heavily armed drug gangs.

For Brazilian girls’ Street Child World Cup team, the football field is a respite from these dangers. “It is my place of safety away from drugs. I used to have a lot of friends who were involved in drug gangs and used drugs. I didn’t know how to cope with that because I wanted something else.” says 16-year-old Rebeca. Her friend Gabby, who plays on the field every day, agrees: “It’s a place where I can dream.”

Through Família Caracol, a Street Child United Brazil initiative that now runs the pitch in Complexo da Penha, they’ve created a space for girls to flourish. “In other communities, people say ‘she’s a girl so she can’t play,’ but here it is normal for us to beat the boys,” Gabby said with a laugh.

“Coming where they come from, it is hard to get an opportunity,” said 21-year-old coach Tammy of their players. Walking to school is often too dangerous and many girls must drop out. Poverty forces other girls into gangs in order to support their families.

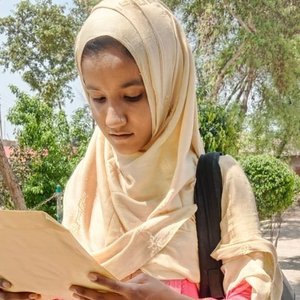

Malala enjoys a game with the winning Street Child United Brazilian girls' team. (Courtesy of Luisa Dorr / Malala Fund)

Jessica, another Família Caracol coach, understands these pressures all too well — she used to be involved in a gang herself. At a young age, she started smuggling weapons and drug across the Paraguayan border. “I didn’t like it, but it paid the bills,” Jessica explained. “I felt like I had no choice.” She turned her life around and left the gang after the Favela Street Foundation helped her become a football trainer. As a coach, Jessica encourages her players to “never give up on [their] dreams.”

Because of Família Caracol, the team’s dreams are getting a little bigger and a little brighter. Following their Street World Cup victory, the girls are setting their sights on other competitions. Rebeca is hopeful for their future: “Football made me believe anything is possible.”

Read more

Read more