Natasha Watley on her Olympic journey and hopes for the future of softball

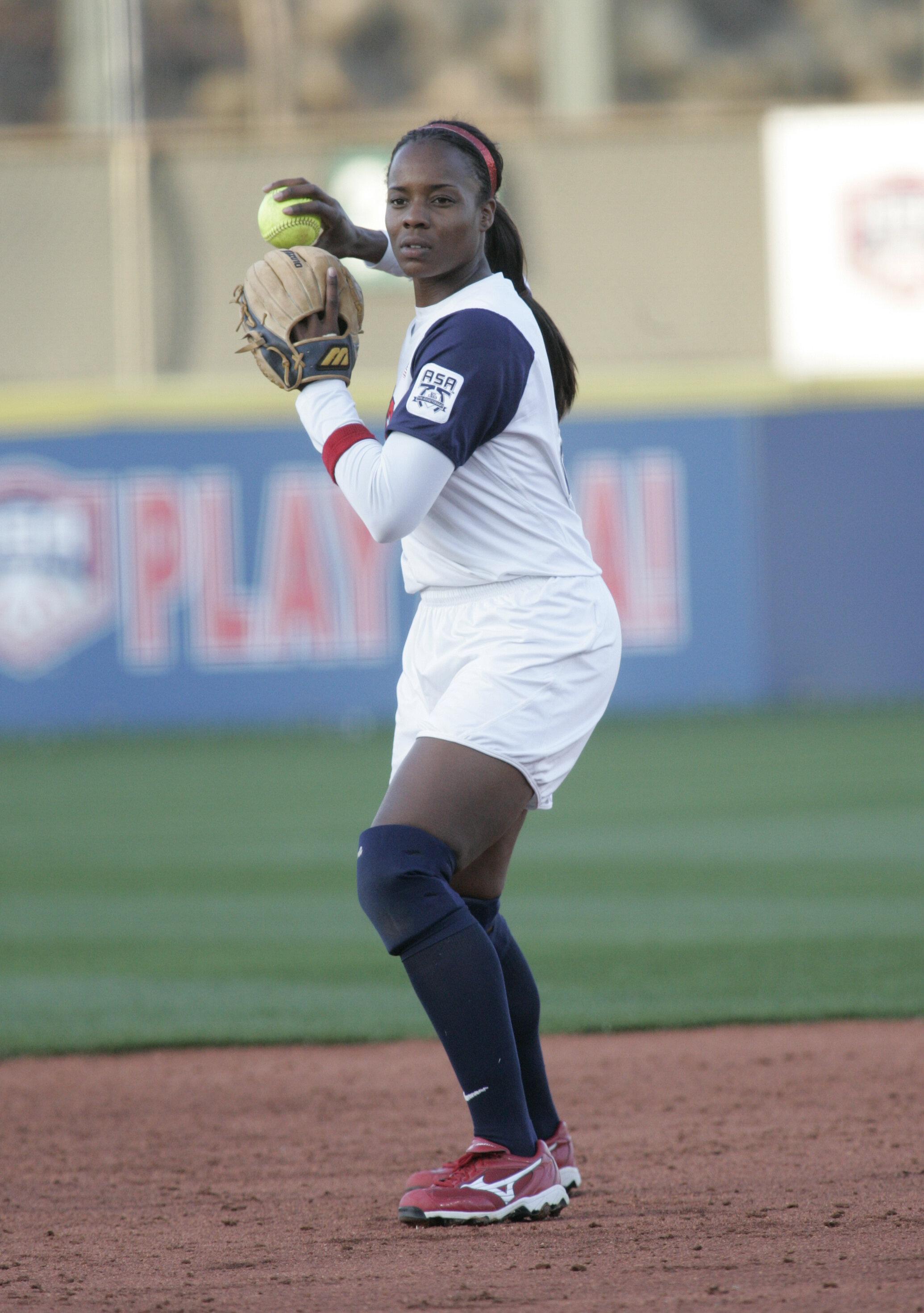

(Courtesy of USA Softball)

With her nonprofit, two-time Olympic softball player Natasha Watley is working to make the sport more inclusive.

It was the mid-'90s and the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA) Bruins were one of the best college softball teams in the country. With seven national championships to their name, these athletes — passionate and full of grit — meant business when they stepped onto the dirt. Then 13 years old, Natasha Watley would travel an hour with her parents to UCLA’s campus to see the team play. Watching the young women of UCLA play inspired her: “For me it became a dream, like: ‘I want to play there. I want to be a Bruin too.’”

(Courtesy of USA Softball)

Natasha started playing softball at age 5. She attended a local clinic with a friend and “instantly fell in love,” she says. “You didn't have to be tall. You could be fast. You could be a great pitcher. You could be a great hitter. I was overstimulated by all the different skills you can get good at.”

If you’re not a softball fan, know this: Natasha Watley did join the UCLA Bruins. She started at shortstop, number 29. While earning her bachelor’s in sociology and minor in African American studies, she became a four-time All-American and earned the third-most career hits in the National Collegiate Athletic Association’s (NCAA) Division I history.

She also went on to become one of the greatest athletes the sport has ever seen.

Natasha is the first Black woman to play softball in the Olympics for Team USA. She is a two-time Olympic medalist, winning gold in 2004 and silver in 2008. She holds the Olympic record for stolen bases. She is a two-time Pan American Games gold medalist and three-time National Pro Fastpitch champion with the United States Specialty Sports Association (U.S.S.S.A) Pride.

Unlike other American sport stars like Serena Williams, Simone Biles or Mia Hamm, Natasha is not a household name in the U.S. But she is famous to softball players like me, one of my childhood heroes who inspired me to become a college athlete.

I was 11 years old in the summer of 2004. There weren't professional teams to follow and college softball was not on my radar yet. All I knew at that point was rec ball: slow-paced and full of errors, with oversized T-shirts for a uniform. It was fun, but the Olympics that year in Athens showed me for the first time how the game was meant to be played.

Natasha, Crystl Bustos, Cat Osterman and Jessica Mendoza (look them up) were the stars of the Team USA softball team, all undeniable forces on the dirt. Screening old footage to prep for my interview with Natasha brought back chills. They were fearless, a team that ran like a well-oiled machine. To anyone who calls baseball a snooze, I dare you to watch softball. It’s faster, higher energy. Similar to how Natasha felt watching the Bruins, I wanted to be like the women on the 2004 U.S. Olympic softball team.

From home plate to first base is 60 feet and Natasha could consistently clock it in 2.6 seconds. She could bunt, slap and hit for power — a triple threat who always kept the opposing team guessing. She hit a .400 batting average in Athens — 12 hits in 30 at bats. In baseball and softball, a .300 batting average is excellent. That year, Natasha helped Team USA defeat Australia to win gold.

Natasha will never forget that moment. She describes seeing the American flag lifted into the air, her family in the stands behind it: “They're cheering. My mom's crying. I'm crying. There's nothing like being able to represent your country and represent the things that matter to you.”

The next year the International Olympic Committee (IOC) made a shocking announcement: The 2008 Games in Beijing would be the last for softball and baseball, which only became Olympic sports in 1996. They were the first sporting events cut in almost 70 years.

With that decision, Natasha’s potential to be a three-, four-time Olympian disappeared. She said it felt like breaking up with a boyfriend, a total heartbreak. Some speculated the IOC determined the U.S. was too dominant or that softball lacked a wide enough global following.

The decision inspired several members of the U.S. Olympic team to help grow the sport around the world. Natasha and Jessica Mendoza travelled to countries like South Africa, Guatemala and Cuba to host clinics and share their expertise and love for the game with other young women.

(Courtesy of USA Softball)

Japan won gold in the 2008 Olympics, Team USA took silver. For Natasha, the loss still stings. She spent the next several years playing professionally in the U.S., then in Japan’s more established league on Team Toyota, before retiring in 2017. But without the Olympics, softball players don’t have a goal to work towards and Natasha feels the sport lost some momentum: “Having female role models, that's something that's not really happening right now in our sport.”

Now she has turned her focus to solidifying the future of the sport. “The coaching is better, competition is better, technology’s better,” she says optimistically. Yet, softball is still struggling with equity and inclusion.

Only 4% of U.S. sports media coverage focuses on women’s sports. When talking about how things have or haven’t changed, in her time competing, Natasha asks if I’ve seen “The Last Dance,” the ESPN and Netflix documentary series she’s watching about NBA legend Michael Jordan. “There was nothing that he did self-promotion wise to have to put himself out there. Literally, he gained respect from being the best athlete.” She paused before continuing, “I feel like women athletes should be celebrated for what they're great at and what they're really able to do, you know, not necessarily on their physical looks. There's a lot of growth... we've got more exposure and people are gravitating to female athletics, but not always for the right reasons.”

Softball is also struggling with diversity in participation, an area where Natasha focuses her work on. “[We need] to continue to provide that access and that opportunity to young girls, no matter their demographic, their race, where they live, what their parents do, it doesn't matter,” says Natasha.

In 2009, she founded The Natasha Watley Foundation to create more opportunities for girls in under-served communities to play softball. She realised the need for an organisation like this while speaking at an event in South Los Angeles. “A young African American girl raised her hand and said: ‘Miss Natasha, your story sounds so cool, but what is softball?’” she remembers. The question shocked her. But then Natasha reflected on her own experience. “I was provided access,” she realised. “I was given an opportunity by growing up in Southern California being exposed to softball. I was allowed to fall in love with this game.”

But growing up, Natasha did not see softball players that looked like her who she could look up to. The sport remains predominantly White, played most often by suburban girls with access to the resources, training and academic programmes needed to succeed. At the collegiate level, NCAA demographics data reveal only 5% of all softball players and 2% of coaches are Black.

Black girls in the U.S. are more likely to attend lower-income, under-resourced schools. Without access to adequate athletic facilities, equipment or trained coaches, research from the Women's Sports Foundation shows Black girls often drop out of sports early or never participate at all. There are also fewer positive representations of Black female athletes in the press.

In an interview with ESPN last month, Natasha said: “One of the things that I regretted during my time being on the national team was not using my voice enough. I thought me visually being an African American woman was enough. Now, given the climate of where we are…I wish that I used my voice more.”

The comment came as part of a response to a major (at least in the softball world) news story about the U.S. pro softball team, Scrap Yard Fast Pitch. The team’s general manager posted a now-deleted tweet tagging President Trump to look at a photo of the players “respecting the flag” as they stood for the national anthem. The post was a dig at athletes who take a knee in protest of police brutality and racial injustice plaguing the U.S. The entire Scrap Yard team quit that same day and reiterated their support for the Black Lives Matter movement. The players have since formed their own team called This Is Us Softball. The story has helped initiate conversations between players, coaches and leadership about how to address the racism players experience and put an end to inequality.

“I'm an introvert and I'm quiet and shy,” Natasha tells me at one point in our conversation. “But that doesn't mean that you can't put your voice out there and put your story out there.”

(Courtesy of USA Softball)

To make it easier for girls to participate in the sport, The Natasha Watley Foundation runs a free softball league in Los Angeles for girls of colour ages 9–18. The organisation provides equipment and practices and games occur at fields close to where girls live. Coaches work with players on building self-esteem, discipline, leadership and team-building skills. They also reinforce the value of education and address issues like body positivity, mental health and social justice.

Natasha aims to recruit coaches for the programme who are representative of the girls they serve and who were players themselves. She wants girls to see that softball is a sport for them. “If they can see it, they can be it,” she says. Natasha would one day like to expand the league across the country and internationally.

“My hope is that girls who have played in the [Natasha Watley Foundation] league go off to college. I hope that they end up coming back and becoming coach mentors so that it's just the cycle that continues,” she says. If they don’t, that’s fine too. More than anything she wants girls to leave with a strong sense of self.

Due to its popularity in Japan, softball will make a one-time return to the summer 2021 Olympics in Tokyo. Nothing beyond that is guaranteed. Still, Natasha is pumped. Upon hearing the news she says: “I kept teasing some of the girls that I know on the team, like I'll be there with my face painted and my flag.”

A couple of Natasha’s old teammates are on the roster, though most are first-time Olympians, a new generation of powerhouses for girls to idolise.

She wouldn’t remember, but Natasha and I met once before in 2006. My travel team attended a clinic hosted by the Philadelphia Force, a pro team Natasha played with that year. We worked on scoop drills and basic mechanics and at the end of the day she shared her story. I asked her to sign a softball for me and it has sat on my desk ever since, a reminder of that day, Natasha’s commitment to excellence and what it felt like to be a girl with a dream.

Read more

Read more