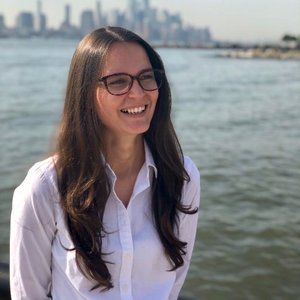

In rural Afghanistan, this chemistry teacher is the solution to her school’s closed lab

(Courtesy of Andrew Quilty / Malala Fund)

Muzhgan, a Teach for Afghanistan fellow, is working to give girls hands-on chemistry experience.

Before Muzhgan arrived, the chemistry lab at the girls’ school in rural Bagram just sat gathering dust. With no qualified teachers, there wasn’t anyone to show students practical experiments. Muzhgan decided to change that.

Muzhgan is a Teach for Afghanistan fellow. Teach for Afghanistan recruits and trains recent university graduates like Muzhgan to increase the number of female educators in the Afghan public system.

For Muzhgan’s first experiment, she demonstrated the chemical reaction of saponification by teaching her students to make soap. The experiment was a hit. Students loved working with the ingredients and seeing the chemical changes occur in front of their eyes.

I spoke with Muzhgan to discuss the importance of experiential learning, why Afghanistan needs more female teachers and her work to convince parents to let their daughters go to school.

Tess (T): What inspired you to become a chemistry teacher?

Muzhgan (M): When I was at school, I was a good student in chemistry. I would force my teacher to do experiments for our class. I desperately loved this subject and wanted to contribute something in this field — maybe become a scholar to work in university. When I saw the shortage of chemistry teachers, I decided to become a teacher.

T: Tell us about reopening the chemistry lab at your school.

Muzhgan conducting a chemistry experiment with her students. (Courtesy of Teach for Afghanistan)

M: The laboratory was closed before I came to this school because there wasn’t a professional chemistry teacher. Other teachers could not even explain the subject well from the textbook, so doing experiments was impossible.

I opened the laboratory to perform practical experiments, because they form the foundation of learning scientific subjects. Understanding without practice is tough, so I decided to take on this initiative and activate the laboratory of this school.

The laboratory does not have all materials for the experiments and it is very often hard to access the required materials. I have to search and sometimes buy it myself from bazar, but it is worth it because practical experiments make it easy for students to learn.

T: How did your principal respond to the success of the reopened laboratory?

M: When we [Teach for Afghanistan teachers] introduced this, the principal said our mere existence in that school is a great blessing for them. Because our presence, students’ attendance increased and they are enjoying their classes.

Additionally, our students can now do experiments even though the school is in a remote area. Due to lack of competent teachers, even schools in the heart of the city in this province can’t do that.

“As a teacher, I aim not only to teach chemistry, but to also transform girls’ mindsets. I motivate them to work hard to change their families’ and communities’ mindsets about girls’ education.”

T: Why is it important for girls to have female teachers?

M: Students feel comfortable with female teachers because female teachers understand their struggles. We give the girls the chance to continue their education. When they have female teachers, families are trusting and do not stop girls from school. If the teachers are male, as soon as girls reached puberty, their families prevent them from going to school.

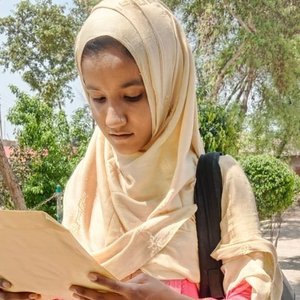

T: What other barriers do the girls you teach face to completing their secondary education?

M: Girls face numerous barriers to education, besides lack of female teachers. One of the factors is families' lack of awareness. For instance, one of my students in grade 11 was stopped from coming to school by her family, because everybody stared at her on the way to school. I went to her parents and convinced them to let her continue her education. I told them to look at me. I come from very far away to teach your daughters. Upon my meeting with this student’s parents, they accepted that I was right and sent their daughter back to school.

There are dozens of students facing the same fate as this girl, which is why we need dozens of teachers like me to fight this situation and bring these girls back to school.

(Courtesy of Andrew Quilty / Malala Fund)

T: How did Teach for Afghanistan help to prepare you for this position?

M: I learned chemistry at school and university, but I did not know how to teach it. Teach for Afghanistan provided me with the pedagogy and educational psychology training and taught me how to relate with lives of the students. Teach for Afghanistan made me what I am today.

T: What do you find the most rewarding part of your job?

M: As a teacher, I aim not only to teach chemistry, but to also transform girls’ mindsets. I motivate them to work hard to change their families’ and communities’ mindsets about girls’ education.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Read more

Read more