A conversation with Tomi Adeyemi

Tomi Adeyemi — author of the global phenomenon “Children of Blood and Bone” — discusses Yoruba culture, representation in literature and why we need to hear from young female writers.

Move aside Harry Potter and Katniss Everdeen, there’s a new young adult hero in town. Meet Zélie Adebola, the strong-willed protagonist of the best-selling West African fantasy novel, “Children of Blood and Bone.” The book follows Zélie on her quest to bring back magic to her people and to fight for her family. Debut author Tomi Adeyemi weaves Yoruba culture — an ethnic group is found in West Africa, particularly Nigeria — into an epic adventure that confronts issues of police brutality, racism and gender-based violence.

Since its release earlier this year, “Children of Blood and Bone” has been captivating readers around the world. At age 23, Tomi reportedly signed a seven-figure deal for the trilogy — which includes a movie deal with Fox 2000 to bring Zélie’s world of Orïsha to the big screen.

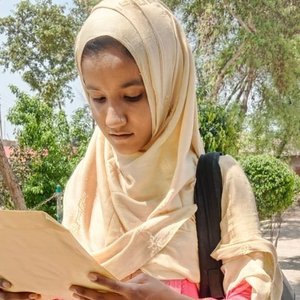

Getting the chance to speak with one of my literary heroes and a fellow Nigerian girl was an amazing experience. I asked Tomi about her inspirations, the importance of representation in literature and what young writers like me can do to succeed. I hope you enjoy our conversation as much as I did.

Omolara Uthman (OU): I know that you consulted your parents on Yoruba phrases for spells and named mountain ranges after family members. Why was it important to you to imbue Yoruba culture into this story and how does it make you feel to see your culture being celebrated by readers around the world?

Tomi Adeyemi (TA): When I first discovered the Orïsha, it was a part of my [Yoruba] culture and a part of my legacy so it was kind of like finding treasure in your own backyard. Once I found it, I decided to lean into it. Something I’ve seen that happens a lot is that people — often fantasy writers specifically — will find a piece of someone’s culture and put it into their writing. But you can’t just take one cool thing and throw it in there. That’s other people’s culture, that’s other people’s heritage, that’s other people’s religions. Once I found it, I was like, “OK, I want to do this right because this is a part of my culture.” This is a very long winded answer...

OU: No it’s fine, I like hearing all of it!

TA: OK, I would say that the way my brain works is like you know when you’re bowling and you have gutter lanes?

OU: Yes, I know those.

TA: For me it’s [writing about Yoruba culture] sort of like that where if I have those little lanes up then my ideas will be a lot more focused and I have more room to be imaginative. When I discovered the Orïsha, the fantasy idea for the world came very quickly. But when I discovered that they were Yoruba, those became like gutter lanes and suddenly the conversation shifts to, “Oh what’s the magical language going to be? It’s going to be Yoruba!” Or, “Oh what are you going to name this? Why not name it after your parents and your grandparents and your aunts? And let’s have fun with it! Let’s not just make something for us, let’s literally put ourselves inside of it and have all the fun.”

OU: So you’d say that you see Yoruba culture as kind of the constraints for the story?

TA: Well I wouldn’t say constraints, but at least the lane with which I can pull from. It’s fantasy blending the real. And so when it came to the culture that’s what I wanted to put in there. You know like when you cough and your mom says pẹlẹ?

OU: Yes, my mom does that all the time!

TA: Yeah! You know it’s like those things that are so intimate to all of our experiences. When you see something like that in a book it’s almost as if someone has written a love letter for you. So I don’t even want to use the word constrain because rather than that they open up the possibilities for this world.

OU: In your powerful post, “Why I Write: Telling a Story that Matters,” you discuss that you write so that readers can see characters that look like them in stories, and also so that readers can fall in love with characters that don’t look like them. What effect do you think that fiction has on shaping people’s outlooks and actions?

TA: Great question! It’s funny because when I graduated college and my first job was in the entertainment industry, something I heard a lot was: “We’re not saving lives here, this isn’t brain surgery.” It’s like we love it, but we understand what role we play. Sometimes I think we downplay our role as storytellers because we create worlds for people to see themselves in and discover other people and learn about life.

It kind of reminds me of this quote by Stan Lee that’s been circulating: “I used to be embarrassed because I was just a comic book writer while other people were building bridges and going onto medical careers. And then I began to realize that entertainment is one of the most important things in people’s lives. Without it they might go off the deep end. I feel like if you’re able to entertain people you’re doing a good thing.”

I feel like with a story like this, it goes even deeper than entertainment, because I wanted to help people see black people, recognize them and empathize with them and identify their pain and feel the need to put a stop to it and fight against it. Whether it’s making sure you vote in a way that doesn’t hurt other people or if that’s seeing a police encounter and stepping up and deciding not to go anywhere or whether it’s a protest, you know? Stories change lives. They touch us and connect us individually and allow us to connect to each other.

“Sometimes I think we downplay our role as storytellers because we create worlds for people to see themselves in and discover other people and learn about life.”

The thing about stories is that we internalize so much. So if you never see a black princess you say, “I can’t be a black princess.” And it might start as a simple thought when you’re young and suddenly it carries on and it’s like, “Also I can’t do this. And I can’t do this. And I’m not enough for this.” It just starts this ugly horrible trail of deep self-esteem issues that I’m still calling myself out. I spent 10 years erasing myself from my own fantasies and my own imagination. I feel very passionate about telling stories and promoting stories that keep as many people as possible — but especially kids and teenagers — from having to do that and having to fight those battles because they’re really hard.

OU: “Children of Blood and Bone” is a fantasy, but it is very much tied to our reality in 2018. Have you heard from your readers about what types of conversations “Children of Blood and Bone” is starting?

TA: That’s the thing with social media is that basically anyone — for better or worse — can comment on your story. But luckily it’s been for better. I’ve heard from teachers that will use an excerpt from “Children of Blood and Bone” and an excerpt from the Laquan McDonald verdict. It’s wild to me to see people write essays and teach my work in a class.

It’s also just informing and mobilizing people and getting the conversations started that I wanted to. The whole purpose of the book is one: to tell an interesting story. Two: to be a mirror for people like us who have never seen ourselves in these types of stories. And three: for people who have seen themselves to show them what’s going on with their neighbors. This is the pain we’re struggling with and I don’t want it to be another hashtag or another story on CNN. I want to really sit there and feel the weight — the impossible weight of living with this fear or living with this grief because the fear has already come true. I don’t think people understand or stop and think about the actual human toll of living in a society like that and living with that fear.

OU: You’ve talked about how the original idea for “Children of Blood and Bone” came to you after you saw a picture of the Orïsha in a gift shop in Brazil and how Zélie and the story came to you after you saw a picture on Pinterest. Tell us more about where your best ideas strike and what advice you have for young writers who have a great idea, but can’t seem to get past that first step?

TA: I love art. I love it so much and I’ve always been a fan of it. Anime is my first love. When people ask me what’s my favorite story I think they expect me to say Harry Potter or something, but no it’s “Avatar: The Last Airbender.” It’s “Naruto,” it’s “Death Note.” Animation has always been so inspiring. Pictures are so inspiring and spark my ideas. Usually I see something and the world for my story comes to me, but Zélie was the first time a character came to me. The advice I would give is look for a pattern amongst the ideas that have inspired you, whether it’s a piece of dialogue or a question. It gets a lot easier because I know images are always going to inspire me so I’m on Pinterest a lot.

OU: Oh yeah, I do that too with the writing tips.

TA: Right and that’s the thing it doesn’t always have to be about writing. People are always like, “Where do your ideas come from?” And it’s very hard to explain to people who aren’t writers that ideas come from everywhere because books are so complicated and there’s so many parts of a book. But as far as that jump off point or that premise, there’s usually a pattern of what inspires people.

I think my first advice to young writers would be don’t worry. I think we put a lot of pressure on ourselves. I feel really grateful that there wasn’t social media and Wattpad and that I didn’t know that other people did fanfiction until like two years ago, because I spent like my entire life writing in complete isolation — nobody saw my writing because I was terrified.

I see a lot of young writers put pressure on themselves to write and they’ll ask me questions like “Is this good enough for publication?” Or “Should I put this on my blog post?” It’s definitely a good idea to put yourself out there to a degree, but a lot of writing is finding yourself, finding your voice and finding your heart. The moment you’re at right now is practice. Like I used to beat myself up for writing 300 pages of Naruto fan fiction and I couldn’t have known at the time that recreating the first 50 episodes of Naruto would help me write battle scenes. Everything you do is training. Even daydreaming is training.

OU: What part of the process of adapting “Children of Blood and Bone” into a movie scares you the most? What part are you most excited about? And will you be playing Zélie in the movie? You had a video on your Instagram at boxing practice and I was wondering is she practicing to play Zélie in the movie?

TA: I’d be super down to be a maji I do not think I have the talent to pull out Zélie but I very much appreciate your confidence in me.

I would say that the scariest part is that despite the fact that I have an editor, the book is still all me — I am the end all be all. With a movie, there are hundreds and hundreds of people coming together to tell a story and as someone who doesn’t like group projects, that is terrifying. Eventually you have to trust people with your book, but that’s also the most exciting part.

“The whole purpose of the book is one: to tell an interesting story. Two: to be a mirror for people like us who have never seen ourselves in these types of stories. And three: for people who have seen themselves to show them what’s going on with their neighbors.”

When Fox told me they wanted to make the movie, I let myself get excited but there were very specific things I want in someone who’s going to be in charge of adapting this movie to the screen. I wanted to know their resumes to see if they made movies I liked. I also wanted to know their intentions: would I have to worry about them trying to cast Scarlett Johansson as Zélie? [American actress Scarlett Johansson faced backlash for “whitewashing” an Asian role in the film, “Ghost in the Shell.”] Or did they know enough that Zélie didn’t just have to be black but she had to be a dark-skinned black girl? You cannot control a movie as an author, but you can control who you get involved with. When you have so many passionate, well-meaning people coming together to do something they are all really passionate about and believe in you, you have the ability to create magic. I feel like it’s going to be magic.

OU: Do we have an idea of when the movie is coming out?

TA: We don’t have a specific date — we have a version of the script and it’s hard to explain to people that it’s good news because we’re focusing on that. “Children of Blood and Bone” is a very tough book to adapt so we’re putting the creative team together and pushing the script further, but my fingers are crossed that filming begins next year and the movie comes out 2020 or 2021. But it’s a complicated thing. It will come out as fast as something like this can come out. But I’m also excited that as much as we all wish it was in theaters today, we’re also very committed to getting it right and building a franchise because we don’t just want one movie, we want the sequel and more. I personally want like “Star Wars”-level spinoffs in 10 years.

OU: I would very much appreciate that. Finally, Assembly has young female readers all over the world and many of them tell us they want to be writers. What advice or message do you have for them?

TA: The most important thing I can say is: you matter, your voices matter, and your stories matter. Whether that’s fiction or poetry or non-fiction or memoir, teenage girls are saving the world right now and they are my entire hope for the future. It’s the most important thing is that people — especially young girls — know that they are warriors and that they matter. And they should write because we need them and we need their stories so that they should create knowing that need is there.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Read more

Read more