Why this Latina tech advocate thinks you should consider a career in government

Vivian Graubard is a technology strategist, diversity advocate and co-author of the new book, “Yes She Can: 10 Stories of Hope & Change from Young Female Staffers of the Obama White House.” (Courtesy of “Yes She Can”)

11-year-old student reporter Anya Sen SAT DOWN WITH Vivian Graubard TO DISCUSS working for the white house, representation in tech and her new book, “Yes She Can.”

Last month, I got to interview Vivian Graubard, technology strategist, diversity advocate and co-author of the new book, “Yes She Can: 10 Stories of Hope & Change from Young Female Staffers of the Obama White House.” I will admit, I was slightly nervous, yet very excited to speak to her.

At 29 years old, Vivian has already accomplished so much. She spent six years in the White House working to improve government digital services for the Obama administration. Her name appears on TIME’s and Forbes’ 30 Under 30 lists. She is an outspoken advocate for diversity and inclusion in technology. I had done my research on Vivian and practiced my interviewing techniques, but I was looking forward to the actual interview the most.

A few minutes into speaking with Vivian, I realized that she was as excited as I was and that had so much to share with Assembly readers. She was accomplished, yet very humble. And I learned so much about her work.

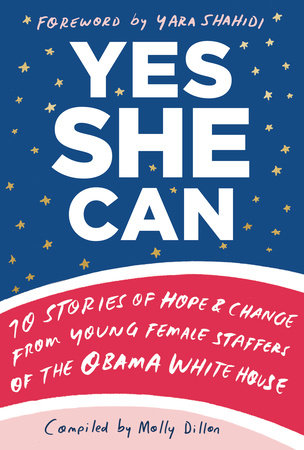

(Courtesy of Penguin Random House)

During our talk, we discussed how Vivian uses data and technology to fight for causes she believes in — her work spans across areas such as human trafficking, immigration and education. Vivian started out at the White House as an unpaid volunteer and eventually co-founded the U.S. Digital Service, where they use technology to improve how people receive benefits.

Vivian writes about her time at the White House in the new book, “Yes She Can,” which hits shelves on March 5, 2019. This collection of essays features the stories of young women who worked for the Obama administration — Vivian’s essay focuses on her work with technology and human trafficking. She hopes “Yes She Can” will help young women realize that government is a “fun and cool place” that also offers you the opportunity to work on issues you care about.

Keep reading to hear about Vivian’s favorite conversation with President Obama, what you need to know if you want to work in government and why she is committed to diversity in technology.

I hope you have as much fun learning about her as I did.

Anya Sen (AS): Tell me a little bit about yourself and where you grew up. How did education play a role in shaping your interests and career?

Vivian Graubard (VG): That is a good question. I'm from South Florida, from Miami. I always loved studying history and government. Those were my favorite things to learn about by far. I always had this interest in politics as a way to change laws and rules and make life better for people.

I think that a lot of education also happens outside the classroom. I grew up spending a lot of time in South America. My family is from Colombia and Cuba. Spending time in Colombia when I was little, I saw a lot. I remember being a little girl seeing a lot of poverty and a lot of children who were poor and did not have homes and were asking for food. And I thought, “That's not fair and the world should look different.” I remember thinking that from a really young age. I think that learning that not everyone is growing up like me and why and how do we make the world more fair for other kids like me is what ultimately led me to want to do this kind of work.

AS: Who was your childhood role model and why?

VG: Oh, that is good question. I have to think about this one. I don't think that I had just one role model. There were a lot of women who I really looked up to, including my mom and my grandmother. My grandmother left Cuba in 1962 and I remember that she would always tell me stories about how hard it was to leave and what the decision to come to the United States meant. She's just one example of a really strong, fearless woman that I’ve always looked up to. I've been really fortunate to be surrounded by a lot of women like her.

Anya interviewing Vivian on video chat. (Courtesy of Tess Thomas / Malala Fund)

AS: She sounds really inspiring. Who or what inspired you to become an advocate for diversity and inclusion in technology?

VG: I didn't actually start thinking about this issue until I went to college when I was taking classes in computer science and technology. I would look around and I realize that I was one of the only women in the class. I had one experience where we were choosing group partners and I didn't get selected on any of the teams, all of the guys huddled together. Another time, we had to pick an issue to work on and think through the role that technology played in that. They were all thinking about one thing and I was thinking about the role of technology in helping impoverished children around the world and access to education. And so we just had these very different ways of thinking and nobody was interested in thinking about solving the problems that I was.

It was through that experience of being one of the only women and one of the Latinas or Latinos in the room that I thought the world should look differently. And in order to do that, we need more diverse people thinking about these problems and using these skill sets to solve big problems.

“It was through that experience of being one of the only women and one of the Latinas or Latinos in the room that I thought the world should look differently... we need more diverse people thinking about these problems and using these skill sets to solve big problems.”

AS: You had a few different jobs during your years at the White House. Can you tell me about those positions? What did you learn?

VG: I started off as an unpaid volunteer in the office of presidential correspondence, which is basically the president's mailroom. If you write a letter to the president, it goes to this office where everything is read and sorted and then every single night, President Obama would read 10 letters from the public. I really liked this office because it was the closest that we got to understanding how people were feeling. You don't have to be rich or have a lot of access or an important person to write a letter. And you had just an equal a chance of the President reading your letter than anyone else did. People wrote in about everything from healthcare to school loans to immigration.

I worked on how we could use technology to digitize the process of reading and responding to these letters. I did that for about 10 months. Then I went to another office called the office of Science and Technology policy where I worked on the use of data, like information, statistics and facts to combat human trafficking and to combat gender based violence. I did that for a few years and then I co-founded a new office at the White House called the United States Digital Service, which uses technology to improve how people receive benefits. There I led our immigration and our criminal justice portfolio. So I was there for about six years and then after the administration ended we left.

AS: What did you learn while you were at the White House?

VG: I learned the importance of context switching and multitasking. The thing about working at the White House was that everything felt important all the time. On any given day, we were working on 10 different things. I'd be in one meeting on healthcare followed by a meeting on education and the next meeting would be on human trafficking. I was constantly having to switch lanes and become an expert at memorizing facts. My brain grew 10 times over that period of time.

I also learned about the importance of listening. I had a boss early on who was such a great listener. He was a really important, really senior person and he always set the tone that we should be listening to one another and never interrupting. It means something when the most important person in the room is listening to you and not interrupting that sort of sets the behavior for everyone else and making sure that you’re understanding what the person in front of you is saying before continuing on.

The Graubard family with President Obama. (Courtesy of “Yes She Can”)

AS: What was the most challenging part of your job and how did you overcome this challenge?

VG: Learning to navigate the White House early on was really difficult. There's no blueprint for how you do this job and it changes with every president and it changes with every new boss. Figuring out how to navigate the building, how to get into meetings, how to be present and raise your hand when there were something that you wanted to work on was really difficult.

I was 21 when I started working there and for a little while I felt really out of place, just being the youngest person there and not knowing how to ask for what I wanted. What I realized with the support of a lot of really great role models was that if I worked really hard and people saw that I was working hard and that I was doing my job well, more opportunities would come my way. And so there was this value in sometimes putting your head down and doing the job and sometimes put in your head up and raising your hand and saying, “I want this.” And finding that balance was really important.

AS: You talked about the role models at the White House who taught you the importance of hard work. Were there any specific people you had in mind?

VG: Oh absolutely. Todd Park was the first. He was one of the Chief Technology Officers of the Obama Administration. He's the one who’s a great listener and he listened to what everyone had to say and was wonderful to work for. The other is Cecilia Muñoz, she’s my boss now and was President Obama's Director of Domestic Policy at that time. She always took time to mentor young women who worked at the White House and to help to empower us and to navigate these sticky situations, like sometimes feeling left out or why wasn't I invited to this meeting or why did this thing happen? She was thoughtful in training us on how to think through how to solve these problems for ourselves.

AS: Is there a project or achievement from your time at the White House that you're especially proud of?

VG: There are. There are so many. One of my first successes early on was translating. Going back to that office of presidential correspondence — the president's mailroom — I discovered one day that if people were writing in foreign languages that they weren't getting responses from the president. They had this policy that they would only respond to letters in English and that they would only respond to letters from U.S. citizens or residents.

I thought, “Well, there's no way to know if someone's a citizen based on a letter.” It’s not like you put that in a letter. And also it's not right to assume that citizens are only writing in English. Like my grandmother, my grandmother would have written a letter in Spanish. So you're actually leaving out all of these people who are writing to the president in different languages and I don't think that's fair. One of the first things that I did was build a system that would translate the letters from foreign languages into English and it would tab them based on subject. This letter is about the environment, this letter is about health insurance. Then I would queue them up for a response in the same way that English letter were being responded too. So President Obama was the first president to respond to a foreign language letter. It was a lot of fun.

AS: Have you ever talked to President Obama? If so what was your most memorable conversation?

VG: I have talked to him. I’ve had a few meetings with President Obama in both the Oval Office and the Roosevelt Room. That's just like a bigger conference room across the hall from the Oval Office. We had meetings on immigration and on the refugee crisis — we had meetings on work things. But my most memorable is not from a meeting. One time I was sitting in the lobby of the West Wing and I was by myself and there was a secret service agent. Do you know what the turkey pardoning is?

AS: Not really.

VG: That’s okay. So the turkey pardoning is every Tuesday before the Thanksgiving break. The presidents have this tradition of pardoning a turkey so they do this whole big event at the White House and there’s a turkey from a farm somewhere in the United States and they basically say, “You are not going to be eaten this year for Thanksgiving.” It's this weird tradition that dates back I don't even know how many years, but they continue to do it year after year.

So it was that Tuesday before Thanksgiving and a lot of people had left early for the break and I was sitting in the West Wing lobby waiting for a meeting and it was just me and this secret service officer and all of a sudden I hear over the secret service officer’s walkie-talkie, “The eagle has landed.” And they start talking about something. I’m like, “What’s happening!” And then I realized that the president is walking into the West Wing. It was him, two of his bodyguards, a policy advisor and some others secret service officers. He walks in and I’m sitting there on the couch. I was really new, this was my first year working in the White House. I’d never seen him in person before. I was like, “Oh my gosh, what do I do? Am I supposed to stand? Should I pretend to write notes so he thinks I’m working and I’m not just like slacking off, sitting on his couch?” He's coming from the turkey pardoning so he’s laughing and having a great time. He looked at me and he says, “Oh hey, how are you doing?” I said, “I'm doing well Mr. President, how are you?” And he's like, “I’m doing well,” and then I just said again, “I'm doing well, how are you doing?”

I was so nervous and he just stood there and looked at me and just stared at me for a few seconds and then was like, “All right then well have a happy Thanksgiving.” The secret service officer was like, “Don’t worry that happens all of the time. People don't know what to do when they see him and they totally panic.” That was my very first encounter. After that it got better, but I was always nervous every time I saw him just because I am a big fan and he was the President of the United States so the shine never wears off. It never got boring.

(Courtesy of Backchannel)

AS: That’s so funny! I read that your harnessed open data to combat human trafficking. Can you explain this a little? How did it work?

VG: Data is statistics and facts that you use to make decisions. But the fact is that we still create policy based on stories and we don't use data to try our decisions. The thing that happens is that you might think that you're doing the right thing, but it's always helpful to have data to measure yourself on.

One of the portfolios that I led was using data to combat human trafficking. It's a space that I feel really passionately about. I was an intern in college at an anti-trafficking organization. When I got to the White House, nobody was thinking about the role of technology in fighting human trafficking and gender based violence. I remember they said to me, “Well, where would we start? What do you want us to do?” I said, “A good place to always start is with data.” Because if you're creating policy around how to combat human trafficking, then you should know where human trafficking is happening, who is at risk, what resources exist to support people, how would law enforcement get involved in tracking down people who are selling other people, right? You need information beyond just stories.

I worked with a dozen agencies and offices and law enforcement groups and nonprofits to begin to collect data so that we can make smart decisions about how to fight human trafficking. One interesting thing is that before they used to always say that the most human trafficking in the U.S. occurred around the Super Bowl. When we looked at the data, however, we realized that that actually wasn't true. And there's a spike for sure, but that’s more because the number of people increases. So a lot of other things increase as a result. But, the fact of the matter is that it's not such an increase that somehow skews how we should be thinking about this.

AS: That’s really interesting. What skills or qualities helped you succeed in your different government positions?

VG: The one that I referred to earlier, context switching and the ability to hold onto a lot of information and listening. Also critical thinking. Somebody tells you something and they're explaining something to you, you should be thinking through like what the next question is. So you're giving me this information, what do I really want to know about it? How do I actually want to solve this problem? What is the next best question to ask?

One of the best critical thinkers I've ever met is President Obama. He asked the hardest, most thoughtful questions at every meeting that had with him. I think if that everybody else accepts what you're telling them as truth and they're like, “OK, OK that makes sense.” But President Obama wasn't afraid to be like, “No, that doesn't make sense to me. Can you explain that to me again? Wait, if you're saying this, then what about that?” So making connections between different issues, critical thinking and analytical skills help drive that. I got better at it over the course of my time there.

Note taking was really helpful. I remember thinking, “Oh, I'll just memorize all of these things.” And then later on I would try and to write something and I'd be like, “Oh, I really wish I had taken notes in that meeting.” And so just being really thoughtful in how we do all of our work was always really important.

“The thing about working at the White House was that everything felt important all the time... I’d be in one meeting on healthcare followed by a meeting on education and the next meeting would be on human trafficking.”

AS: Have you ever met with someone whose life has been impacted by your work? If so, what was the experience like and how did it make you feel?

VG: I have. A lot of our work is centered around users, the person who ultimately needs a policy or a program. And so I've had the good fortune of being able to work with the people I'm serving on multiple occasions and every single time it's really moving. It's also really hard because these are difficult issues.

I remember meeting with people who were waiting on their immigration benefits to come through. They had applied to apply for a specific visa and they were waiting to hear back whether they got it or not. That’s really difficult, because they're worried, they're afraid they might not get it. It's very stressful. Ultimately my job is to take all of their concerns and all of the things that they find confusing about a process and use that to make the process better for the next person. I might not be able to fix it immediately, but if I understand what about their experience was difficult or scary, then maybe I can use that to fix it for someone else who might be applying for the same thing in the future.

AS: Now on to your book, “Yes She Can,” which is being published on March 5. Can you tell us a little about what we expect to read from your essay?

VG: Yes! I actually write about my tech and human trafficking work in my essay. Specifically I write about a trip that I took to Mexico with the United Nations, the State Department and organizations who are working in the anti-human trafficking space. We were meeting with parents whose children had been trafficked. So it was a hard trip. We were doing a few things. One is that we were teaching them how they can use technology in their own advocacy work and to protect themselves. We were also there to listen to them, to listen to their concerns, to understand their experience, how it had affected them and what if anything we could do to help them or help prevent this from happening to anyone else in the future. A lot of my essay centers around our time in Mexico, which was the first international trip that I took at the White House. And it was really, difficult. It was really emotional. And it was also life-changing.

The authors of “Yes She Can: 10 Stories of Hope & Change from Young Female Staffers of the Obama White House.” (Courtesy of “Yes She Can”)

AS: What do you hope young women will take away from reading “Yes She Can”?

VG: My number one hope is that young women will see that our government is only as good as the people who show up to work in it. I hope that they see that government can be a cool and fun place to work. I think that right now people don't feel that way. They don't see it as a place where you can go and create change. And I think the opposite. Each one of the co-authors writes about an issue that was really close to them, close to their hearts, even before they got to the White House. It's almost like government is a place where people can go and work on whatever it is that they think is most important. What is the issue that you care about most in the world?

AS: Girls’ education.

VG: Girls’ education, perfect. There are so many offices and agencies across the government at a local level, the state level, the federal government level where there are people who are thinking about girls' education. If you want to have a hand in crafting what the future of girls’ education looks like, then the government is the place to do that. Each of us we sort of found that opportunity to work on the thing that we care about the most inside of government. And I think that most people may not know that's even a possibility.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Read more

Read more