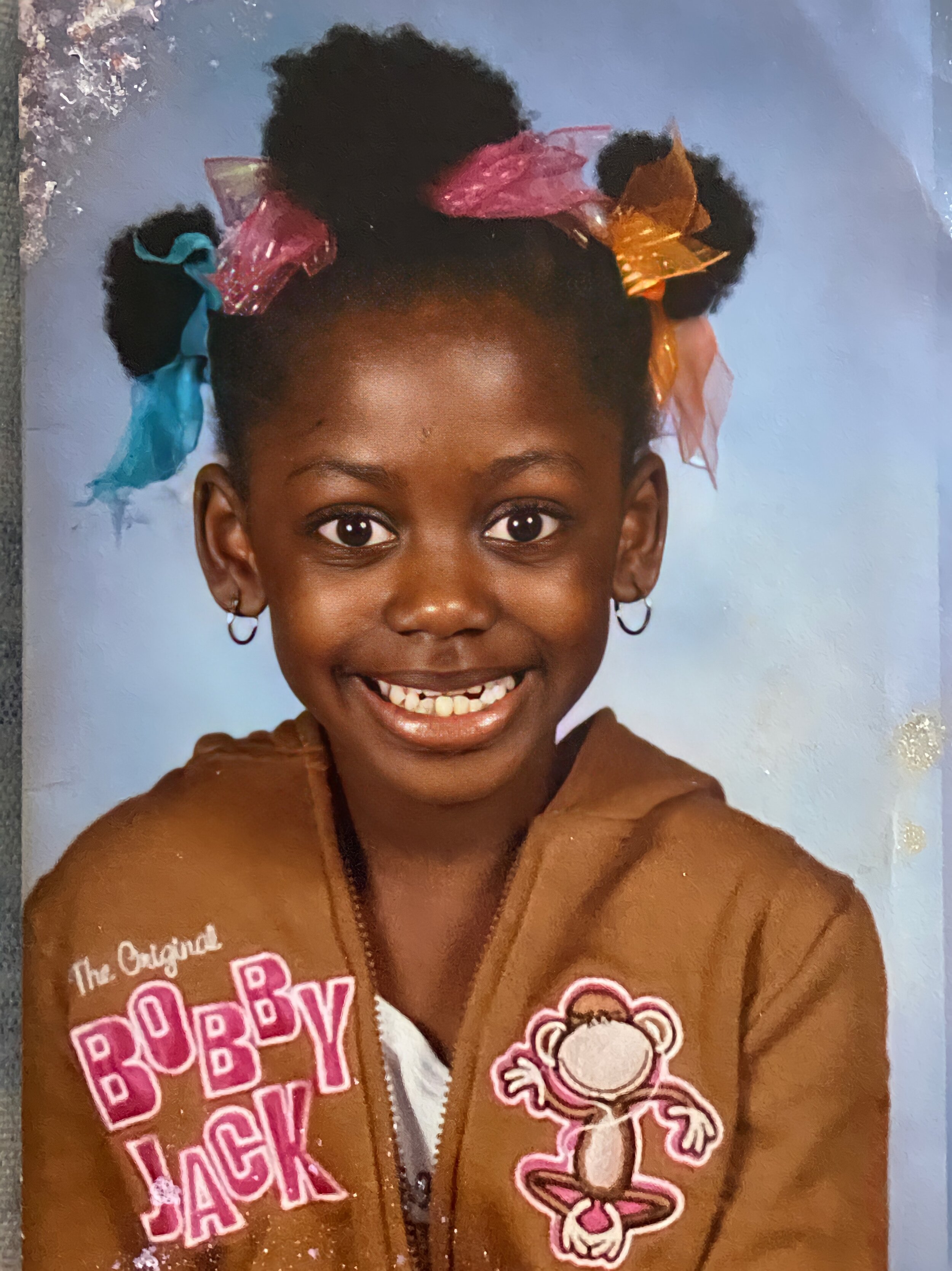

How the world fails little Black girls

(Courtesy of TK Saccoh)

21-year-old anti-colourism student advocate TK Saccoh investigates intersecting oppressions that contribute to the erasure of Black girls.

Before I had the words to express myself, I noticed that the world treated Black girls differently and dark-skinned girls even worse. In 2005, I moved to the United States from Sierra Leone. At my elementary school in Washington, I was the only Black girl in every class until the third grade. Nobody, not my teachers nor my peers, let me forget this. I became that Black girl, a case study for curious White children convinced that I was related to the only other Black person they knew, Barack Obama. I was the Black girl everyone turned to stare at when my second-grade teacher taught my class about slavery. My happy grin in school photos belied the discrimination I experienced every day at school. I was Black first and a child second.

In 2009, my family moved to Philadelphia where I attended a predominately Black school. Young and naive, 9-year-old me thought my days of being bullied for my appearance were over. However, a new kind of bullying emerged. It was not the racism I was used to in predominantly White settings, but it was just as insidious. It was something I did not have the language for, yet felt so familiar. It underscored my transformation from that Black girl to that dark-skinned African girl. It was colorism, and it followed me everywhere. I was dark-skinned first, Black second and a child last. I was never allowed to lead with my childhood.

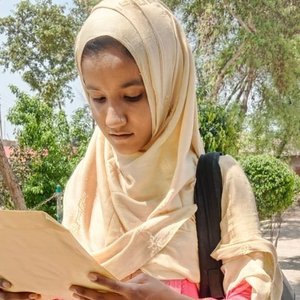

(Courtesy of TK Saccoh)

Like a typical bibliophile, I turned to literature to investigate why my complexion did not come with the carefree bliss of childhood and why adults and children alike were invested in stomping out my light. With Toni Morrison’s “The Bluest Eye,” I arrived at a painful answer. Morrison skillfully captured my feelings of neglect, invisibility and shame within the novel’s protagonist, Pecola Breedlove. Pecola was an 11-year-old dark-skinned Black girl who everyone thought was ugly and ignored. Everyone she encountered was committed to destroying her confidence. Pecola’s family, friends and sometimes strangers measured their humanity and worth against her perceived ugliness. She endured ugly systemic treatment — abuse, trauma and extreme poverty — which ultimately drove her to insanity.

I see Pecola in myself and all the Black girls this world has demonized and forgotten. The world is critical and unforgiving of Black girls. Large social justice movements are born out of the deaths of Black boys, yet the world rarely stops to mourn missing and abused Black women and girls. A paradox emerges from our simultaneous erasure and hypervisibility; the world doesn’t see us, yet the world constantly appropriates Black girls’ aesthetics and vernacular. We are only “seen” to the extent to which it benefits others.

“The world is critical and unforgiving of Black girls. Large social justice movements are born out of the deaths of Black boys, yet the world rarely stops to mourn missing and abused Black women and girls. A paradox emerges from our simultaneous erasure and hypervisibility; the world doesn’t see us, yet the world constantly appropriates Black girls’ aesthetics and vernacular.”

This brings me to Ma’Khia Bryant, a 16-year-old Black girl who was fatally shot by a police officer in Columbus, Ohio on April 20. Ma’Khia Bryant was not a dangerous, knife-wielding “woman,” as many are making her out to be. She was a frightened child who tried to protect herself from being jumped by two adults. She was twice failed by the state, a foster child who called the police for help only for them to kill her upon arrival. It's important to consider how Ma'Khia's size — in addition to her Blackness — affects the way people perceive her shooting. Popular tropes like the “fat bully” impute fatness to immorality and aggressiveness. In “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone,” J.K. Rowling uses this dangerous stereotype to describe her story’s bully: “Dudley was very fat and hated exercise — unless of course it involved punching somebody.” In fat Black children, adultification intensifies because people tend to associate size with aggressiveness, as they do with Blackness.

I explore these issues among others on The Darkest Hue, a digital platform I created in June 2020 to combat the systemic erasure of Black girls, especially dark-skinned Black girls. In a recent post, I investigated the dire consequences of adultification and found that Black children are six times more likely to be fatally shot by police than White children. Not only that, Black girls are more likely to be suspended, expelled and arrested compared to White girls, and adults perceive Black girls ages 5–19 to be less innocent and need less protection than White girls.

In a society that cannot distinguish Black children from Black adults, the future of Black girls is precarious. In a society that privileges spectacle, the perceived invisibility of Black children can be fatal. White supremacy never remembers Black girls but, like muscle memory, it never forgets how to break us. Black girls deserve safety, opportunity, rest and play. Black girls deserve empathy, compassion and protection.

Read more

Read more