patent pending

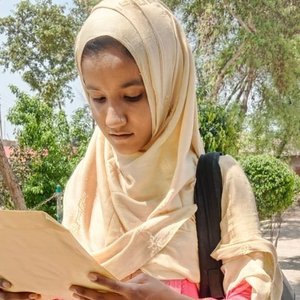

Slam poet and student Shnayjaah Jeanty shares her poem about Black name stereotyping and how Black people reclaim their identity and power with their names. (Courtesy of Shnayjaah Jeanty)

Slam poet and student Shnayjaah Jeanty shares her poem about Black name stereotyping and how Black people reclaim their identity and power with their names.

The African American community boasts thousands of intricate, unique monikers that defy the standard for names in the U.S. Hyphens, apostrophes and letter capitalizations other than the first letter are hallmarks of this beautiful culture. However, schools, businesses and other institutions often disrespect and discriminate against Black names, deeming them “ghetto.” Name stereotyping is an unfortunate symptom of being Black in America. From the day their names are first uttered, Black individuals are subject to intense ridicule and nicknaming that reduces their culture to a laughingstock.

African American names leave a distinguished legacy on birth certificates, paperwork and signatures — all of which name stereotyping aims to erase. In my mother’s country Jamaica, “Jah” is the Rastafarian name for God. My name, Shnayjaah, is a prayer. A nod to a higher power. However, living in a country plagued by racial implicit bias has made my name feel powerless. Every first day of school, I notice at least one person quipping that my mother was inebriated when she named me. Since I was 11, students would call me “Nigger-nayjaah” or “Sh-nigger.” Despite several reiterations of the proper pronunciation of my two-syllable name, people regularly refer to me as “Shanaynay,” a reference to a made-up name for a stereotypical “ghetto” Black woman. So the culture of Black naming — making one's child stand out in a world that systemically strives to put them down — is a bold affront to prejudice that we should respect, not ridicule.

“African American names leave a distinguished legacy on birth certificates, paperwork and signatures — all of which name stereotyping aims to erase. ”

In America, Black individuals are not only stifled by their skin color, but their names. Statistically speaking, job applications with “Black sounding” names are less likely to be accepted — regardless of qualifications. This specific issue perpetuates the wage gap between Black people and their White counterparts. The chasmic gap is what prevents many Black individuals from sustaining themselves and their families without reliance on government assistance. When a minority group is forced into the low socioeconomic status that they are socially categorized in, escaping that income bracket becomes immensely difficult.

Moreover, name discrimination represents racism often disguised as harmless jokes or dark humor. When one refers to a name as “ratchet,” or applies made-up names like “Bonquisha” to African American culture, they attempt to tear Black people from the progress they’ve made in distancing themselves from their stereotypes. By diminishing Black names to a racially palatable synonym without their permission, they endanger an African American’s sense of pride.

“As a Black girl who has adapted to the judgment that follows introducing herself, I used to resent my parents for cursing me with such a ‘ghetto’ name. Today, however, I know that my name is not ghetto, but inventive.”

As a Black girl who has adapted to the judgment that follows introducing herself, I used to resent my parents for cursing me with such a “ghetto” name. Today, however, I know that my name is not ghetto, but inventive. I’m grateful to them for giving me a tool that has shaped me into the activist I am today. With my poem “patent pending,” I wanted to depict my anger at our society's system of hate, as well as pride in a community that makes our names something we'd want to live up to, names that command full attention. “patent pending” addresses the freedom that my name represents while acknowledging this freedom’s absence in today’s social climate. I hope to attack a form of racial stereotyping that often determines our social, academic and financial success. Any Black person should read it and feel honored to have their name.

Above all, I want the public to look past the “ratchet” stereotype and see the beauty in Black naming. It is our duty as Americans to ensure that this country mends its past transgressions. Compared to other attempts to destabilize systematic racism, this one only requires a change of perspective.

patent pending

before you name my mother negro, christen her inventor

my name,

the lightbulb—

the mechanical sun—

built by petty fingers of a woman who wanted to snap america’s opening the same way i did hers, wet and thunderous

my name,

the telephone—

the travelling conversation—

each twisted tongue drools in reparations

phonetic retribution for men with palms and teeth like westward expansion

praying is a lot like missed call, so mama learned to worship the dial tones

before you call my name ratchet, label it legacy

my name,

malcolm x—

reclamation “by any means necessary”—

violent graphite protest against looseleaf sheets

pariah of its own motherland

don’t you know that securing liberty has never been peaceful?

the rubber bullet aftershock of my name should shatter crowds

reminder of what that dark skin girl with that “tacky” name is capable of

my name,

langston hughes—

a lettered representation of exactly what happens to a “dream deferred”—

my name is gold, god, and glory

each vowel braided between escape routes and rice grains

stolen african literature swelling your tonsils into freedom bell

america is the doorstop to a room that never asked to be opened and our names reinforce locks

my name is black excellence

is being related to martin luther king, jr. and harriet tubman

because every slave heir is your brother and sister

is the scion of a culture that speaks more cemetery than english but still remembers to live

before you shoot my brother, look at his hands

black names,

the only adjectives capable of describing this black magic—

for black boys with apostrophes freckling their names—

which is to say, that black boys are edited into contractions

which is to say, that black boys are something that needs to be shortened

the police academy is training assassins

primed to sever each syllable into staccato

translating my government name into a death wish

turning our black skin into white flags

the education system fails african-american students in more ways than an F

most of our high school careers don’t receive a suffix

instead we hold vigils for the people we could have been

before you name my mother negro, christen her protector

our names,

an alphabetic SOS—

yet we are raised to be our own saviors—

i carry the name of every murdered african-american on my birth certificate

on my license and registration as i wonder if the afterlife is just as dark as my skin

black names were destined for more than gravestone etchings

i am still struggling to find a name for a country that spits in the faces of the people who invented it

Read more

Read more