The young women fighting to save Chinatowns from gentrification

Audrey Chou, Mai-Anh Peterson and Amy Phung are fighting to save Chinatowns in their communities from gentrification.

As Chinatowns around the world reel from racial and economic injustice, young women are organising to save these iconic neighbourhoods.

For 17-year-old Audrey Chou, Flushing, Queens — home to one of New York City’s largest Chinese communities — has always been a special place. One of her favourite childhood memories is passing the food vendors that lined the neighbourhood’s bustling Main Street — especially the vendor selling fresh yóu tiáo, a Chinese breakfast food made of fried dough.

Now, Audrey rarely sees any vendors at all. In 2018, the city passed a bill banning street vendors in Flushing, citing that they were “sidewalk obstructions.” The gradual disappearance of street vendors isn’t the only change the community has seen. In recent years, small local businesses have been pushed out in favour of large companies and retailers. A shiny new mall — complete with luxury condominiums — now sits just across the street from public housing reserved by the city for low-income residents. The number of new boba shops has increased, but so has the price of rent. Traces of what made Flushing’s Chinatown such a culturally rich and unique community are slowly disappearing because of gentrification — the process by which wealthier newcomers move into a historically working-class and low-income area, increasing the cost of living and forcing longtime locals to move out.

Throughout history, Chinatowns around the world have served as important cultural havens for Chinese immigrants in predominantly White countries to shelter from racial discrimination and which later survived by catering to visitors searching for a glimpse of Chinese and Asian culture. But these communities are quickly disappearing because of displacement and growing anti-Asian racism that have drastically lowered tourism.

Flushing is not the only Chinese immigrant community at risk. Regular immigration raids hurt shops and restaurants in London’s Chinatown. Redevelopment is forcing out essential businesses that serve the residents of Toronto’s Chinatown. And Montreal’s Chinese community faces similar threats from real estate developers.

As Chinatowns around the world reel from racial and economic injustice, read on to hear from the young women organising to save these iconic neighbourhoods.

Audrey Chou — Flushing, New York, U.S.

Audrey Chou is a 17-year-old high school student and youth leader of the MinKwon Center for Community Action’s Youth Organizing Committee. Audrey has helped campaign against the rapid gentrification of Flushing and started the Protect Flushing initiative.

Audrey Chou is a 17-year-old high school student and youth leader of the MinKwon Center for Community Action’s Youth Organizing Committee. (Courtesy of Audrey Chou)

What does Flushing mean to you?

For a lot of the Chinese diaspora and first-gen Chinese kids in New York City, Flushing is that place for them — whether it be where their doctor's office is, where the orthodontist is, where their favorite restaurant is. Most young people growing up in Queens feel a really strong connection with Flushing. And I think that's also what makes people want to fight for it so much.

Have you witnessed the firsthand effects of gentrification and displacement in Flushing? If so, what do those look like?

The biggest thing is the changing food landscape in Flushing. People often know Flushing as a kind of “foodie” place; people that come here for restaurants and stuff. But a lot of the shops that have been in Flushing for decades have been relegated to really small hole-in-the-wall-type restaurants, while there's been a lot more space made for more trendier restaurants that have been getting a lot more traction. Although they're still Asian foods, it's a very catered taste made by transnational corporations and these developers who come in and try to curate Flushing as a more “high-end” dining place now as opposed to what it used to be.

“People often know Flushing as a kind of ‘foodie’ place; people that come here for restaurants and stuff. But a lot of the shops that have been in Flushing for decades have been relegated to really small hole-in-the-wall-type restaurants, while there’s been a lot more space made for more trendier restaurants that have been getting a lot more traction.”

Much of the work that you do as a youth activist in a Chinatown is related to advocating for affordable housing (housing reserved for low-income and working-class residents) especially as the price of rent increases in a neighbourhood like Flushing. Could you tell us more about that?

A lot of people are acutely aware of the fact that housing is essentially everything. Where you grew up — and especially in places like New York, where your education is dictated by your zip code — is a vehicle for social mobility. Everything in your life is affected by where you live, whether it be your environment, your health care, education, the resources you have access to, the food you can eat. That's what makes it so important to me; I realize that it's so deeply interwoven.

Project Flushing is a youth-led initiative to stop luxury development — gentrification — in parts of Flushing, and many high schoolers are involved. What advice do you have for others on balancing school and activism?

I think the biggest thing is rooting yourself in why you are organizing, because if you're doing it for the wrong reasons, it's always going to feel like a chore, tiring and a burden on top of your schoolwork. But as long as you place yourself in these groups that you are genuinely, genuinely enthused about, you'll have all the time in the world.

Mai-Anh Peterson and Amy Phung — London, U.K.

Mai-Anh and Amy are co-founders of besea.n, a nonprofit, grassroots organisation founded by six East and South East Asian (ESEA) women working to promote positive representation of ESEA people in the U.K. and tackle discrimination at all levels of society.

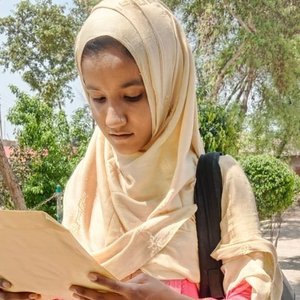

Mai-Anh (pictured) and Amy are co-founders of besea.n, a nonprofit working to promote positive representation of ESEA people in the U.K. and tackle discrimination at all levels of society. (Courtesy of Mai-Anh Peterson)

Why is London’s Chinatown so important to you?

Amy: I grew up in London, so I visited Chinatown in London quite often. To me, it was almost a gateway to another world, because I grew up in a primarily White neighbourhood. I had many friends from different backgrounds, but I didn't have many friends that were from East or Southeast Asia, apart from maybe going to Chinese school. So it was really great to be dragged to Chinatown by my mum for groceries — the different smells, different foods, different languages that you hear. I really enjoy going there because it was like a bit of home away from home.

Mai-Anh: One thing I do really like about London's Chinatown is that it's become a space that's not just for Chinese people; it’s become a place that's really important for the ESEA diaspora. “Chinese” probably isn't even really the appropriate designator because there are so many Hong Kong, Cantonese and people from mainland China. There are Taiwanese places. There are lots of Malaysian-Chinese [people] in London. Increasingly, Chinatown has become a place where there are Japanese, Indonesian and Vietnamese restaurants. It's become more of an inclusive space.

While London’s Chinatown has been subject to discriminatory immigration raids in the past, do you think racism against ESEA people — from xenophobia and COVID-induced racism — in the U.K. has amplified prejudice against Chinatown?

Amy: I think it's had two different kinds of effects. There’s obviously been instances of overt racism towards residents and businesses in the area. There's been vandalism happening and increased reports of hate incidents within the area. It has caused a kind of reckoning among the community there, because there are almost two sets of people living there. The new businesses that have come in are run by younger business owners who are not necessarily from China, but from lots of different parts of East and Southeast Asia, and they are really on social media. They can talk about [anti-ESEA racism]; they've been spreading news about what's happening. And then there are the people who are the original people who have had businesses for a long time in Chinatown and actually don't really want to address it, don't really want to talk about it. They may know that these things are happening — the increased uptick in racism — however, they would much rather put their head down and carry on.

Mai-Anh: I think the intergenerational aspect is a really important one, because we see that most of the organising is coming from the children of people who own restaurants and takeaway places in the U.K.. They've been raised in the U.K. and that experience during their formative years is very different to that of their parents who were preoccupied with running a business, with putting food on the table, with survival. For the kids who grow up in a majority-White society, it's a very, very different experience, and they're also of an age and a demographic that uses social media much more, so there's more exposure to the ideas that are circulating.

What has an organisation like besea.n done to bridge the generational divides between newer, younger ESEA residents in Chinatown and older ESEA immigrants?

Amy: We have actually been part of a workshop [for Chinatown residents] that we [are running] where we [are] talking about building advocacy skills, talking about finding collective voice, acknowledging intersectionality and how we can help each other in different ways, because I think people view advocacy and even activism as people holding banners and signs and protesting and causing a ruckus. That’s why there are so many different ways to do it, and there are definitely efforts to try and get businesses — people who are within the Chinatown community — to really start taking advantage of using their voice to help people in the area to make it a more inclusive space and a safe place to visit and allow them space to talk about any issues they have going on.

Amy Phung is a co-founder of besea.n. (Courtesy of Amy Phung)

Mai-Anh: One of the most amazing moments was with one of the older women who attended the workshop, at the end of the feedback session. We had introduced the term “microaggression” and we weren't sure how that was going to go down with older generations, who typically are a bit resistant to talking about racism and tend to have more of an approach of “just get your head down and get on with it.” But she stood up and said, “I finally have a term to describe this thing that's been happening to me all my life that's been really upsetting to me. But I never had the language to talk about it. And so now I know what that is.”

Hazel and Jenny* — Toronto, Ontario, Canada

Hazel and Jenny are volunteers for Friends of Chinatown Toronto, a grassroots group fighting for housing justice, economic justice and racial justice in Toronto’s downtown Chinatown.

Why is Toronto’s Chinatown important to you?

Hazel: Any city I go to first, the first thing I do is go to Chinatown. There is a culture of safety in that neighborhood that just draws you there; there's comfort provided there and there's a community provided there. If we acknowledge that we live in a White supremacist society, then this is the society that's going to try to separate us from our history continuously, so people will do that work of reconnecting, keeping those bonds strong but also relearning and reformulating what Chinatown means. This is a dialogue we have to keep alive.

How has gentrification impacted the community here?

Jenny: There’s been a loss of some essential services, like the loss of Oriental Harvest, which was an East Asian grocery store. As an effect of COVID too, small bakeries have been evaporating, and as these mom-and-pop businesses that serve the neighborhood disappear, so do the residents who live in the neighborhood. We have another neighborhood, Koreatown. Koreatown is interesting because there are mostly businesses, but no Korean people actually live in that neighborhood. And so we're slowly seeing Chinatown becoming less and less of a livable neighborhood and more and more a pop-up tourist kind of neighborhood.

Hazel: You see Chinatown sort of adapting to cater to a more middle-class, upper-class demographic now as a result of their pricing, as a result of how housing is built. These are places that are not meant for folks to lay down roots; it's really becoming a sort of stopping point as opposed to a destination point because of the sort of pricing pressures. Chinatown [is being] presented as an economic and tourist destination, as opposed to a place where people can just sort of be. There's always this push of economic development and tourism. When you talk about culturally specific neighborhoods, for instance, it's like, “What kind of revenue, or interest or cultural capital is it going to bring to the overall city?” This is language we hear from politicians all the time in terms of what the state of the community is in the larger scheme of things.

“Chinatown [is being] presented as an economic and tourist destination, as opposed to a place where people can just sort of be.”

How has COVID-19 and the resulting anti-Asian xenophobia affected Toronto’s Chinatown?

Hazel: Canada is really interesting because there is explicit racism, of course, but there's also the institutional and systemic racism that people don't think of as often. We'll see politicians try to make efforts such as hate [crime] legislation, when policing in our neighborhood is also anti-Asian. Homelessness in our neighborhoods — without addressing the systemic concerns of why people are houseless — is also anti-Asian. Food insecurity in our neighborhood — the result of these grocery stores being torn down — I would argue, is also anti-Asian racism. It can take many shapes and forms, and I think [systemic issues] are going to be the things that are more difficult to advocate for, because it's not a White lens of what racism looks like.

On a similar note, what do you make of recent “stop Asian hate” movements that have been spurred on by police or security surveillance footage — and which often lead to calls for policing and incarceration?

Hazel: FOCT [Friends of Chinatown Toronto] is an abolitionist group. We don't work with cops. We don't believe in policing. In our neighborhood, over-policing is definitely not the answer because you have so many undocumented folks here. One of the reasons [FOCT is] running a low-barrier access vaccine clinic [in Toronto’s Chinatown] is because so many folks don't have health cards. They don't want to give their ID. Policing always happens after the fact. It's not a preventative measure, which is something that we just don't support. And of course, it's rooted inherently in policing the Black and Indigenous communities in Chinatown as well.

Wawa Li — Montreal, Quebec, Canada

Wawa is a 24-year-old fashion designer living and working in Montreal. She volunteers with the Chinatown Working Group, which raises awareness among advocates for and defends the interests of Chinatown users and residents in Montreal.

Wawa is a 24-year-old fashion designer who volunteers with the Chinatown Working Group in Montreal. (Courtesy of Wawa Li)

Your organisation has been sharing stories from Chinatown residents on social media. Can you share a particularly interesting story or interaction you've heard from or that you've had with a Chinatown resident or community member?

I was walking with a [Chinatown] senior, because the seniors always hang out at the same spot together. I went for a walk with one of them and we were just walking the whole street, telling me little inside jokes about the other seniors, and it was really cute. One of the reasons why I'm working hard for [Chinatown Working Group] is actually this little community of people that already exists, like the seniors. As with the elders of my family, I'm thinking about my parents when they're older. I want them to have the same environment as these seniors right now, and without this community, this will not happen.

Chinatown in Montreal is very small now and it's continuing to shrink in size. Have you experienced firsthand how gentrification is affecting Chinatown?

Right now, we're experiencing changes: The building that [real estate developers] just bought is Wing Noodle, which is one of the oldest noodle factories. We're going to see it being erased right now. When you take the time to look, most of the buildings are vacant, not even preserved. It's disgusting inside, but I just know from elders who have lived in Chinatown that before there was Complexe Desjardins, which is a huge mall, this was part of Chinatown. That was like a huge chunk that [the mall developers] took away. Chinatown is like three streets now. Even Sun Yat-sen Park, where there was grass and places to sit, now they’ve put tiles on it and it’s less and less of a park. I know that the rents are also very expensive.

“I want this to be in everybody’s brain: It’s not just a Chinese matter, it’s a cultural matter. If you care for real history to be taught in your school to your kids, it’s now that you have to speak up.”

What sparked your interest in activism?

I just started [with Chinatown Working Group] three months ago, when [a shooting of Asian women] happened in the [Atlanta] spa. I remember it was so hard for me. The whole week I was not understanding what was going on. I was late to work. I was on Instagram and people were just posting and I was like, it's cool to post, but I was like, “Am I ready?” I've been told to continue, to go on. I was like, “I'm not ready. I'm not ready to see the truth.” And then when I was ready, I saw it and I was like, [“I’m] going to have to speak.”

What do you wish people knew about Montreal’s Chinatown?

Chinatown is not a Chinese matter. I want this to be in everybody's brain: It’s not just a Chinese matter, it's a cultural matter. If you care for real history to be taught in your school to your kids, it's now that you have to speak up. It's not just a Chinese matter. We all have to understand that this is our problem and it's affecting everything just like a domino or a wave in the ocean.

*Editor’s note: Hazel and Jenny are pseudonyms.

Read more

Read more